Listen to the audio

Listen to the audio

If there was one principle the Founders wanted to make clearly understood in their new system of government, it was who makes the laws for the United States. They believed this power to make law should no longer belong to a king, dictator, or oligarchy. It would belong solely to those who the people elected to public office for the purpose of making laws in their behalf.

They also clearly stated that these lawmaking powers should not be delegated to just anyone, especially to a person or entity that was not directly elected by the people. As if to emphasize this point, the Founders made this the very first subject in the Constitution. Article I, Section 1 states that:

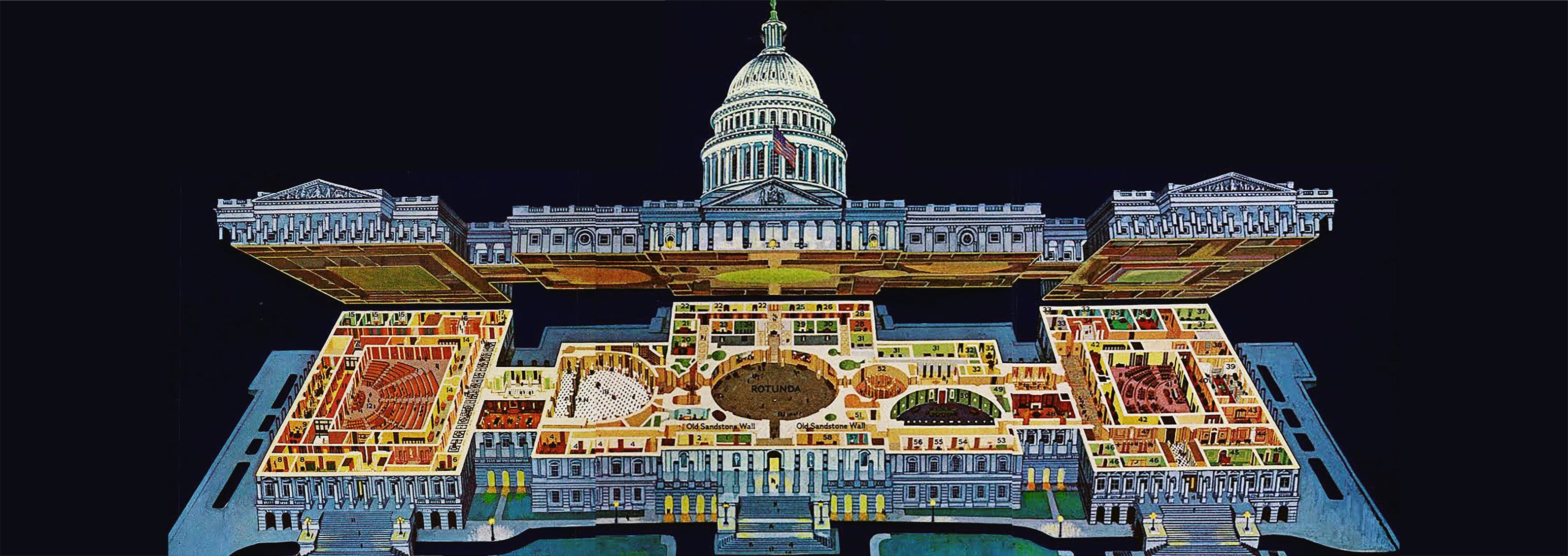

"All legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives."

As with nearly every other provision of the Constitution, this affirms a particular right of the people. It announces to the whole world that in America, people do not consider themselves subject to any law that has not been thoroughly examined by the people’s representatives.

To illustrate how the founders envisioned the lawmaking process to work in their new system of government, let’s look at a law-making pattern they left between the lines in the third amendment. Although this amendment is often skipped over, it is useful to better understand the balance between individual rights and how laws should be created to protect collective rights.

The Third Amendment prohibits the government from sheltering soldiers in private homes without the homeowner’s consent. Since this has never been an issue, the third amendment has received little consideration. Let’s look at the amendment more closely.

“No soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.”

Amendment three guarantees that the government cannot require private citizens to provide a Soldier with room and board unless he or she willingly consents to the arrangement. This amendment recognizes that everyone has a right to life and is free to obtain and dispose of property. They have the right to choose who comes into their house, and when. These are some of our natural rights that no one, including government, should violate.

In addition to our individual right of consent, this amendment illustrates how the Founders choose to protect this right in a collective sense. It states that soldiers could be quartered in our home during times of war, but it would need to be done “in a manner to be prescribed by law.” This qualifier, “to be prescribed by law,” is critical as it illustrates how the Framers chose to protect our collective right of consent in society.

We do not lose our right of consent in time of war. Rather, we pre-consent through laws passed before the war. While it is unlikely that we would be asked to quarter soldiers, this phrase adds extra emphasis to the wisdom of the Founders in placing “all [law-making] powers. . . in a Congress of the United States. . .” We consented to this because we know that laws affecting our life, liberty and property cannot lawfully be passed without first being thoroughly discussed by representatives of our choosing within the limits we have placed around them.

As originally conceived, the American lawmaking process was just about as foolproof as the Founders could make it. Their legacy to future generations included a limit on the powers and responsibilities the elected representatives of the people could operate under. For example, James Madison explained that:

"The powers delegated by the proposed constitution to the federal government are few and defined." Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution lists about twenty areas in which Congress is authorized to make law. Any laws enacted outside these few and defined areas was considered unconstitutional and a blatant usurpation of power.

As the Constitutional Convention drew to a close, Oliver Wolcott of Connecticut praised their new creation. He specifically mentioned the two chambers of Congress – the Senate and the House of Representatives – which represent the States and the People respectively. “They will therefore be the guardians of the rights of the … citizens” he said. “So well guarded is this Constitution throughout, that it seems impossible that the rights either of the states or of the people should be destroyed."

Now, nearly 240 years later, it is clear that Wolcott was far too optimistic. We have strayed significantly from the founder’s original system. The Federal Government has usurped so much power that it is difficult to list an area in which they don’t have an influence in our lives. Thus, we are now subject to more laws that don’t go through Congress than do. In addition, Congress no longer feels any restraint by the specific areas of responsibility delegated to them in the Constitution.

Oliver Wolcott saw a document that embodied principles of freedom and self-governance, but he assumed that people would be jealous of their freedom and be proactive in preserving it. What happened, and will almost always happen, is people take freedom for granted. They assume the people they elect will do what’s best for them. They forget the truth that Daniel Webster taught.

“There are men, in all ages…who mean to govern well; but they mean to govern. They promise to be kind masters; but they mean to be masters…. They think there need be but little restraint upon themselves…. The love of power may sink too deep into their own hearts….”

If we want good laws that will maintain our freedom, we must follow the time-tested advice of James Madison.

“A well-instructed people alone can be permanently a free people.”

So, in answer to the question, “Who Makes the Laws for the United States?” We do!

3 comments

James C Prentice

“It is not the function of our government to keep the citizen from falling into error; it is the function of the citizen to keep the government from falling into error.” — U.S. Supreme Court in American Communications Association v. Douds 339 U.S. 382, 442 (1950)

John

“Power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely!”

Bill