Listen to the audio

Listen to the audio

Just ten years before Thomas Jefferson died, and after many years of observing people in offices of political power, he commented: “Our legislators are not sufficiently apprised of the rightful limits of their powers….” He could have made the same observation in our day nearly two centuries later. Evidence is plentiful to show that when people are elected to public office, and especially after they have been in office awhile, they begin to feel that the legitimate power of government extends to about anything they want as long as they can get enough votes to do it.

Any student of the U. S. Constitution can easily outline the limits of power of the federal government. That document gives Congress, for example, the power to do about 20 things which can be itemized quickly by reading Article I, Section 8. The 10th Amendment clearly limits the federal government to those express powers outlined and says that all other powers remain with the states and the people.

Although the tenth amendment is violated daily on the national level, no Congressmen can plead innocent of knowing the tenth amendment prohibitions – they are there for all to see.

Whether or not the power of government is spelled out in constitutions, honest legislators should be bound by higher principles of conduct toward those whom they serve. These higher principles should ring so loudly in the ears of public officials that even in the absence of specific written limits, they should know their bounds.

It is hoped that a discussion of these higher principles will provide a better understanding of the legitimate power of government and the proper role of an elected public official within that government. These principles are timeless, as is their application.

The Origin of Human Rights

Any discussion on the power of government will always lead the honest student back to the question: “Where did our human rights come from?” There can be only two possible answers to this question. Either they were given by God, or they are granted by government. If one concludes they are bestowed by government, then one also must accept that their basic human rights can be defined by government. The Founding Fathers flatly rejected this concept as evidenced in the Declaration of Independence. “We hold these truths to be self-evident,” they declared, “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” They further defined the “pursuit of happiness” as the right to have and enjoy the fruits of one’s labors.

Volumes have been written attempting to prove that human rights were God-given, but to the Founders it was so logical and self-evident, the discussion need not be carried further. All individuals have the same God-given rights. This is the first premise to our discussion.

Reduce the Complex to the Simple

Remember when you were faced with a difficult problem in math, chemistry, or physics and it looked impossible to solve because it was so complicated? What did your teacher tell you to do? Break it up in small understandable units and solve it a step at a time. That is especially true today in the field of computer technology.

We have found this method very effective when trying to analyze political questions. Since people existed before government, what kind of rights did the people have when there were no governments and just a few individuals? The answer – the same rights to protect one’s life, liberty and property that we have today. God given rights have not changed just because we have more people or because we have formed governments.

The Origin of Government

Each of us have the right to stay up all night and watch for intruders who might try to steal our property or threaten our lives. We also have the right to remain close to home with our garden hose ready just in case our house catches fire. We have the right to protect our lives and our properties – two essential elements of our freedom. But none of us want to spend all our time doing those things. So, we get together and agree to pool our resources and hire a sheriff and a fireman. At that moment government is born. The people have created public entities to serve them.

What Authority Does this Government Have?

When citizens band together and, for efficiency sake, hire others to do something for the good of the whole that they could individually do for themselves, they each give the hired servants certain limited authority. Can the servant do more than what is authorized by the master? Does a sheriff or a fireman automatically accrue more authority with the passage of time? Do the public servants automatically have more power to do more things just because more people join the community? It is clear to see in this example that no authority can be given that the individual didn’t possess before government was created. The authority of the public servant can never rightfully be greater than that of the citizens individually. Government has no innate power or privilege to do anything. Its only source of authority and power is from the people who created it. People can give to government only those powers as they themselves have in the first place. Since individual people created government to protect the individual’s unalienable rights, it follows that the person is superior to the creature that was created. The creator is superior to creation and should remain master over it. Even those who do not believe in “God-given rights” can appreciate the logic of this relationship. Proper government activity lies within delegated powers and no further. Individuals cannot delegate to government a power they do not have in themselves.

Suppose Mr. Jones decides he needs an automobile but doesn’t have the money to buy one. The Smith family next door have two cars, so Mr. Jones decides he is entitled to share in his neighbor’s good fortune. Is he entitled to take his neighbor’s car? Obviously not! If the Smiths wish to give it or lend it that is another question. But so long as the Smith family wishes to keep their property, Mr. Jones has no just claim on it. If Mr. Jones has no power to take the Smith’s car, can he delegate any such power to the sheriff? No. A person cannot delegate a power he does not have.

Even if everyone in the community desires that the Smiths give a car to the Jones’, they have no right individually or collectively to force the Smiths to do it. What if they held a public vote on the issue? The answer is the same. Even if the vote was 99 to 1 in favor of the Jones family, individuals cannot delegate a power to government they themselves do not have. This principle, as explained by John Locke, was clearly understood by the Founders of our country: “For nobody can transfer to another more power than he has in himself…”

The Key to Proper Government Activity is Individual Conscience

Government, then, is limited to only those spheres of activity within which the individual citizen has the right to act. The principle is this: People should commit no act in the name of government which would be wrong for them to do as individuals. The inherent nature of a good or an evil act is unaffected by changing the number of people involved in its commission. If an act is good and proper for an individual acting alone, it is good and proper when done in concert. An act which is evil or improper when done by an individual is equally evil and improper when done by a group, even when the group is acting in the name of government. The rightness or wrongness of every act performed in the name of government, then, can be determined by applying the test of individual conscience. This is the fundamental key to determine the limits of governmental power.

Two of our great Founding Fathers recognized the importance of public policy having its roots deep in the moral code of the individual. George Washington said, in his first inaugural address, “….the foundation of our national policy will be laid in the pure and immutable principles of private morality.” Benjamin Franklin stated: “He who shall introduce into public affairs the principles of primitive Christianity will revolutionize the world.”

If I Would Punish, then the Government Can Punish

Another important test of proper laws is this: If it were up to me as an individual to punish my neighbor for violating a given law, would it offend my conscience to do so? If punishing my neighbor would offend my conscience then I should never authorize my agent, the government, to do this on my behalf.

When individuals give their consent to the adoption of a law, they are specifically instructing the police (or government) to take either the life, liberty or property of anyone who disobeys that law. This may sound extreme but unless laws are enforced, anarchy results. Therefore, individuals should be attentive to the laws passed by their representatives lest the law allows punishment in violation of the individual’s conscience.

What Then is the Legitimate Power of Government?

The fact that government officials have no right to do to the citizens that which the citizens have no right to do to one another is succinctly stated by Jefferson in the following words:

“Our legislators are not sufficiently apprised of the rightful limits of their power; that their true office is to declare and enforce only our natural rights and duties, and to take none of them from us. No man has a natural right to commit aggression on the equal rights of another; and this is all from which the laws ought to restrain him; every man is under the natural duty of contributing to the necessities of the society; and this is all the laws should enforce on him; and, no man having a natural right to be the judge between himself and another, it is his natural duty to submit to the umpirage of an impartial third. When the laws have declared and enforced all this, they have fulfilled their functions, and the idea is quite unfounded, that on entering into society we give up any natural right. The trial of every law by one of these texts, would lessen much the labors of our legislators, and lighten equally our municipal codes.” (Jefferson to Francis W. Gilmer, June 7, 1816)

Jefferson enumerates the three areas of legitimate government activity:

- Punishing Crime

- Compelling each person to bear his fair share of the cost of government, and

- Arbitrating and enforcing rights between citizens.

He states that every law may be tested by one of these three requirements.

Temptations of a Politician

The political arena provides a most effective way of exercising control over someone else. Numerous examples in history could be given of individuals or groups which have sought control of government as a means to control the activities, property (including money), and even the thinking of large numbers of people.

Political power is like military power. Normally, a person does not achieve this power because of his goodness, his honesty, or his high morals. He achieves prominent positions of power if he can persuade enough people to support him. Gaining political power is many times a function of how much money one has available or how he can otherwise manipulate public opinion. George Washington expressed concern that Americans would forget that government is force. Said he, “Government is not reason, it is not eloquence –it is force! Like fire, it is a dangerous servant and a fearful master!”

People who hold political offices, then, are in extremely sensitive positions. One decision can mean the livelihood of many people. One decision could mean the success or failure of a whole industry.

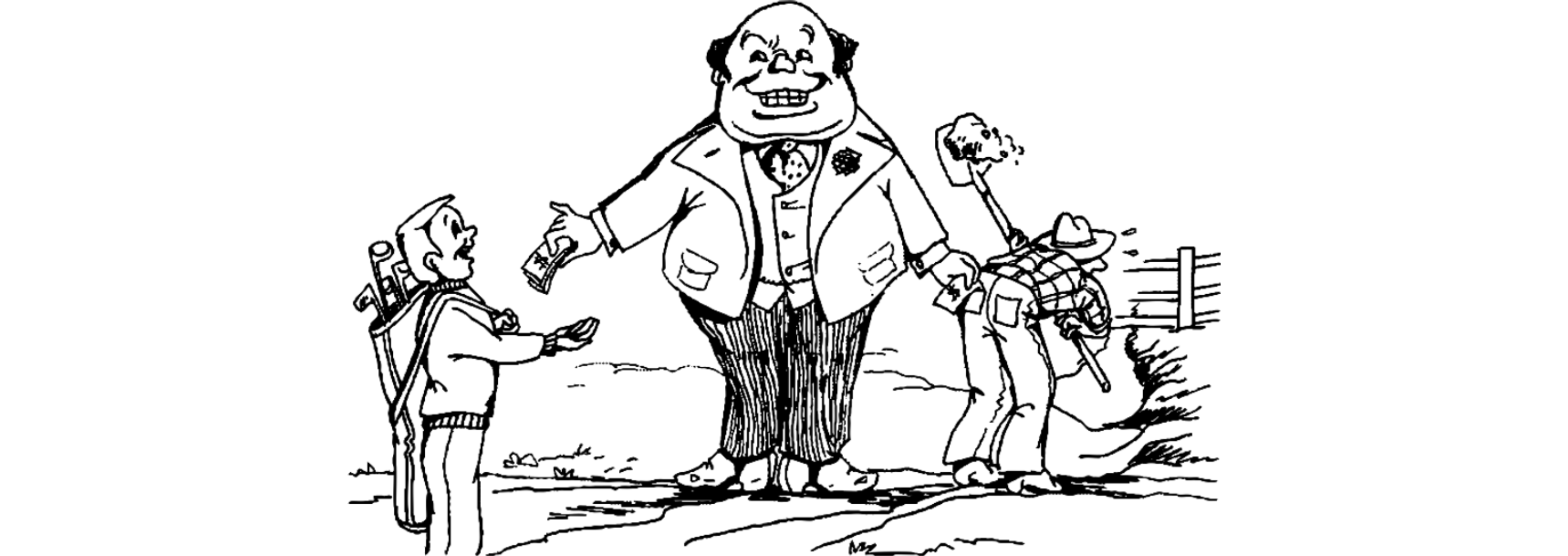

Benjamin Franklin said there are two temptations which beset a politician –the love of power and the love of money. The temptation for a politician to do through government what an individual would not have the right to do, that is, to take from the “haves” and give to the “have-nots”, is a very powerful temptation indeed, and although government has no authority to do such a thing, nearly every politician succumbs to the temptation to do it anyway. Such activity directly violates the equal protection of life and property – principles upon which our republic is based.

Let’s teach these principles to our children and spread them to all we know. Faith requires action and it takes a lot of faith to remain free.

6 comments

Chuck

These weekly posting are a true extension of personal knowledge – if anyone is brave enough to consider and test against their assumed knowledge. I find most people are neither – brave enough to consider that they are not as smart as they “think” they are on so many subjects.